Methane (CH4)

Methane has long been considered a harbinger of climate catastrophe. According to NASA, “what we know for sure is that a lot more methane (CH4) has made its way into the atmosphere since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution.” Human activity has increased the amount of methane, similarly to carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere, contributing to climate change. We know this because methane concentrations in the atmosphere have gone up ~150% since the preindustrial age.

Methane Passes 1,900 ppb

According to data released by the EPA, atmospheric methane (CH4) concentrations in parts per billion (ppb) remained between 400–800 ppb in the years 600,000 BC to 1900 AD, and since 1900 AD have risen to levels between 1600–1800 ppb. Global averaged monthly mean atmospheric methane is currently at ~1900 ppb CH4, increases between 8.8 ± 2.6 through 2017 compare to an average annual increase of 5.7 ± 1.1 ppb between 2007 and 2013. Methane reached record levels in the atmosphere in 2021 – here’s why that matters: it could lead to a climate “tipping point. 1900 ppb surpasses the recommended limit of approximately 1250 ppb (Hansen et al). This should alert us to a fire alarm moment for humanity.

Methane is known to have a greater greenhouse gas (GHG) warming factor than CO2, a potential of 34 times that of CO2 over 100 years according to the latest IPCC Assessment Report. The IPCC thinks almost half of all global warming to date could have been caused by methane. Just to put this into perspective over several time frames the IPCC AR5, widely cited as an authority on this matter, reports that the 100-year global warming potential (GWP) of methane is 34, the 20-year GWP is 86, the 10-year is 99, and the 5-year GWP was found to be 115. Even more recent research has upped the GWP of methane somewhat additionally, by around 25%.

Even more troubling is that recently, researchers everywhere are finding that methane readings globally are spiking. Many experts are noting a surging trend and recently, shocking data has emerged showing global atmospheric methane readings literally going off the charts (video). But is this because of anthropogenic, natural or Arctic methane sources? There are many questions surrounding the methane mystery. Let’s take a closer look. Also, this is being actively discussed on the SW Facebook Group. Join us and join the discussion!

“Welcome to the baffling world of methane studies, where there’s a vast amount at stake for the planet but, often, little clarity about the questions that matter most.”- Washington Post, February 2020.

Methane by the Numbers

To briefly summarize from methane by the numbers, according to Dean et al. [2018], “anthropogenic sources are slightly larger emitters of methane to the atmosphere compared to natural sources.” But these anthropogenic sources aren’t getting much attention. In fact, the methane threat from anthropocentric sources has been significantly downplayed by mainstream reports. Even those who are concerned about methane emissions seem to focus solely on natural sources (i.e. the Arctic). Methane emissions from human activities are almost never mentioned by mainstream reporters or environmentalists, even though methane emission levels have reached emergency status. Most people seem to be completely unaware that we are in a methane emergency. In short, we know about CO2, but not CH4.

Methane is a hard-hitting greenhouse gas. Anthropogenic sources of methane, from fossil fuel mining, rice agriculture, raising livestock (cattle and sheep), and municipal landfills are a huge concern and responsible for some 60% or more of this problem. IEA’s methane tracker confirms that the top anthropogenic emitter of methane is agriculture, read animal farming, with the fossil fuel industry a close second.

Now scientists say we’ve dramatically underestimated how much human activities are playing a part here. “What we’ve previously categorized as natural methane emission must be anthropogenic sources, the most likely being fossil fuel use and extraction,” Hmiel said. Further, University of Rochester professor and study co-author Vasilii Petrenko noted that the difference is “a factor of ten,” at least, between prior estimates of geological, fossil methane sources, such as underwater seeps, and the very low volume of these emissions that their study suggests.

However, those sounding the alarm bells about methane often focus, almost obsessively, on Arctic methane fears. But the Arctic’s contribution to the global methane budget is estimated to be a fractional .0003 GTC/yr or .03% of the total global methane budget according to some estimates by experts like Dr. David Archer. Still, “scientists have long feared that thawing Arctic sediments and soils could release huge amounts of methane, but so far there’s no evidence of that,” says Ed Dlugokencky, an atmospheric chemist at the NOAA.

Among natural sources, which account for less than 40% of the overall methane emissions (see Methane in 5 Pie Charts), wetlands are the top culprit. But the concern continues to center around the Arctic sources. The fears emerge because of the incalculably massive quantity of stored Arctic methane hydrates (video), which if released, do threaten to double atmospheric methane and other greenhouse gas concentrations, including CO2, in short order.

Additionally, recent methane readings in the Arctic have been alarming for the past couple years at least and elevated since 2007. Scientists are seeing never before recorded measurements and seas boiling. NASA flights recently detected millions of Arctic Methane Hotspots. Yet, another study suggests higher levels of naturally occurring fossil methane, argues Stefan Schwietzke, a researcher with the Environmental Defense Fund. He cited a recent study finding emissions of 3 million tons per year just from one sector of the Arctic ocean.

The methane story unfolding now is complex, full of contradictions, and potentially lethal. Experts are working to understand it, but more research is needed to determine how to handle this emergency situation being caused by human activities. There is also the formidable question of the risk of firing the infamous clathrate gun, which will be discussed below.

“Scientists in Siberia have discovered an area of sea that is “boiling” with methane, with bubbles that can be scooped from the water with buckets. Researchers on an expedition to the East Siberian Sea said the “methane fountain” was unlike anything they had seen before, with concentrations of the gas in the region to be six to seven times higher than the global average.” – Newsweek, October 2019

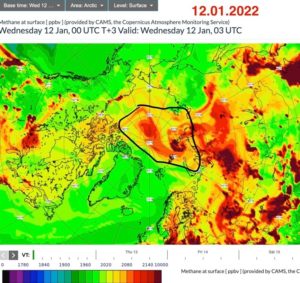

Methane Recordings Are Off The Charts in the Arctic, January 2022

There is a large methane plume over the Arctic now reaching the North Pole. This big spiral over the North Pole is a new feature, but there are massive emissions all over the area. Some coastal areas are showing high readings near Yamal. And there continue to be high readings, literally off the charts, even over water which is anomalous. The readings are showing 2300+ ppb concentrations effectively maxing out the ability of the satellite to measure it. We suggest contacting Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service to ask if they can update the charting.

It is very clear that the recently crossed methane milestone of 1,900 ppb is driven by human activity (which comprises 60% of methane emissions); and we cannot afford to forget that. But now the natural sources are showing significant signs of stress (also because of us). This is a clear case of “the warming feeding the warming,” says methane expert, Dr. Euan Nisbet. We are in the danger zone.

Excessive Methane Readings Reported in the Arctic

Around 1250 ppb (parts per billion by volume) is the energy or ‘heat balance’ for methane. This approximation was established by Dr. James Hansen, Former Director of the NASA Goddard Instituted for Space Studies. We are currently at about 1860+ ppb for CH4. At atmospheric concentrations over 1250 ppb, this powerful greenhouse gas contributes to excessive heating of the Earth. This figure was stated in Dr. Hansen’s book, ‘Storms of My Grandchildren.’ Recent methane readings in the Arctic have been extremely high.

The latest methane readings reported by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in the Arctic have been in the red zone and higher. Trends in methane can be found on the NOAA trends tracking ESRL page. The following chart from NOAA shows a lot of red. The pink coding in the Arctic indicates the extreme high end. Methane readings are typically noted by researchers in the troposphere, where weather happens, is at approximately 450-500 millibars. Readings are now well above vanguard numbers for methane to date, see chart:

Additionally, the first active leak of methane from the sea floor in Antarctica has been uncovered by scientists. The research, published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, reports the discovery of the methane seep at a 10-metre (30ft) deep site known as Cinder Cones in McMurdo Sound. It is a 70-metre long patch of white microbial mats, and a second seep was found during the 2016 expedition.

Recent Methane Spikes Reported

According to Randall Gates, Science Communicator, “I’ve been commenting about the unusual spike in methane at Barrow since last summer when I first began noting it. It has now showed up on flask and in-situ data for over 6 months. Dozens of readings spanning months well above 2000 ppb. Industrial? Oil & Gas operations? Other?”

The methane signal that has been visible since last summer is visible from Copernicus CAMS and has been very consistent throughout the winter months. The link shows methane concentration at 500pa (about 5,500 metres (18,000 feet) to 11,000 metres (35,000 feet) above the ground. It turns out that oil and gas leaks are a big part of this problem. Again, fossils fuels are to blame.

In fact, recent studies show that anthropogenic and industrial methane have been severely underestimated. They found that methane emissions from natural phenomena were far smaller than estimates used to calculate global emissions. That means fossil-fuel emissions from human activity — namely the production and burning of fossil fuels — were underestimated by 25 to 40 percent, the researchers said.

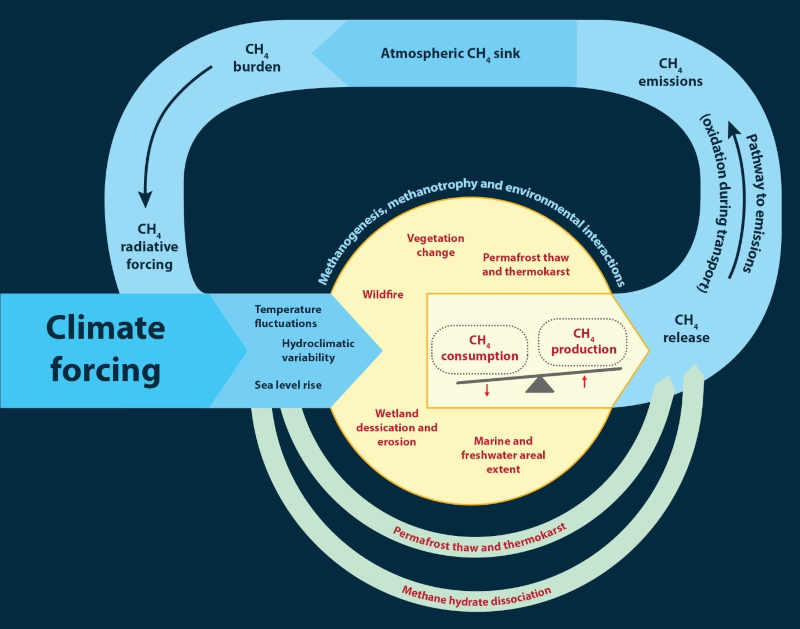

The Warming is Feeding the Warming

In an interview, Dr. Euan Nisbet said that “methane is growing fastest over the Arctic and then over the tropics.” High methane readings in the Arctic, he explained, are largely due to the Siberian gas fields. The bulk of the rise in the last 10 years in the tropics is primarily from burning fossil fuels. This is in turn heating bogs and wetlands which are already a major source of methane. Dr. Nisbet said this is how the “warming is feeding the warming”. This is becoming a common phrase among researchers.

The current research is pointing to man-made methane as the clear culprit underlying these impacts. Anthropogenic sources are exacerbating and speeding the natural response from the Arctic. In short, the current methane emergency is caused by human activities. This emergency is because of us, and it is up to us to curtail it. We can no longer stop it. But there is still some evidence that we might mitigate some of the worst outcomes if we cut emissions fast according to experts like Michael Mann and James Hansen. This discussion will unfold as we take a look at methane fact versus the fiction.

Arctic Methane: A Catastrophe in the Making

There’s tons of this potent greenhouse gas locked up in icy crystals worldwide in the Earth’s cryosphere — more than the total remaining fossil fuels. When it comes to the crystal form, known as methyl hydrate, the perceived threat is so great, that there’s a collection of scientists that have formed the Arctic Methane Emergency Group (AMEG).

Arctic methane release from natural sources, to be distinguished from industrial sources, is the release of methane from seas and soils in permafrost regions of the Arctic. There are also many miles of wetlands in the Arctic. Methane release from these areas is typically considered long-term natural process, but it is heavily perturbed by man-made global warming and polar amplification. This results in staggering negative effects and dangerous feedbacks that researchers postulate could result in lethal releases over time and quite possibly a much feared runaway event could be triggered.

For this reason alone, many notable climate scientists and climate justice workers have said that it’s time to declare a methane emergency. Other researchers have postulated a methane bomb scenario, or abrupt release from Arctic hydrates. This has made methane a dramatic and controversial topic of late. There are many factors involved. The Arctic methane cycle is often misunderstood. In the following video lecture with Dr. David Archer, climate scientist and methane hydrate expert, a full lecture on this topic is provided:

Methane Ice Quick Facts

Methane hydrate or “methane ice,” is the most common type of gas hydrate. Hydrates sequester vast amounts of carbon in the global system. These mysterious gas hydrates (video) are frozen highly concentrated form of methane trapped in clathrates. Different estimates put the total amount of clathrates in the Arctic at anywhere from 5,000 to up to 10,000 GTC, more recent reports have put this estimate at just 1800 GTC (video), but no one knows for sure how much there is. According to Rupple et al, “an estimated 99 percent of gas hydrates are in ocean sediment and the remaining 1 percent in permafrost areas.”

The National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) summarizes this issue as follows suggesting further study is needed before we jump to any conclusions:

“there are two potential sources of methane in the Arctic. The first source of methane is called methyl clathrate. (,,,). We’re not sure how much methane is trapped in methyl clathrates, or how much is in danger of escaping. (…) The other major source of methane in the Arctic is the organic matter frozen in permafrost. This is why permafrost carbon is important to climate study.”

We do know that gas hydrate is condensed within cage-like molecules. For every 1m3 of hydrate there are 180m3 of trapped compressed methane inside of it. Warming a small volume of gas hydrate could thus liberate large volumes of gas. This means a relatively small amount, packs a big punch.

Hydrates are widespread in the sediments of the marine shelves, permafrost areas, and locations where ocean and atmospheric warming can disrupt hydrate stability and drive abrupt releases. In very cold regions like the Arctic, clathrates even occur on the shallow continental shelves or on the land in permafrost, the deep-frozen Arctic soil that does not even thaw in the summer.

Additionally, remember that it’s not just CH4, but also even more CO2 and other greenhouse gases, that get released when these ancient stores of carbon are provoked from their slumber in the cryosphere. Methane ice is stable at very low temperatures under moderate to high pressure conditions in the stability zones. What causes release, or as it’s more technically known, the dissociation of methane hydrates is still poorly understood. This is a science in its infancy.

The question is could these vast stores of methyl hydrates currently locked up in the Arctic inventory be triggered to dissociate prematurely due to human activity and, if so, when and how much? This is a mystery many researchers are trying to unravel. In a warming world, the heat threat to these frozen assets is significant. Furthermore, the frightening potential for a large, abrupt release from sequestered clathrates from marine sediment or permafrost or both due to rising sea and air temperatures is taking science to task.

For even more details on the fundamentals of methane hydrates >>

Clathrate Primer on SW’s Methane 101

Subsea and Terrestrial Permafrost Methane

Methane release from beneath lowland permafrost represents an important uncertainty in the Arctic greenhouse gas budget. Permafrost thaw shows signs of abrupt, irreversible climate change degradation greater than previously expected, according to a University of Colorado study released in February 2020. Permafrost is defined as ground, including rock or (cryotic) soil, at or below the freezing point of water 0 °C (32 °F) for two or more years. Many permafrost areas have been frozen since the last ice age, about 11,000 years ago, and some has been around for more than a million years. These areas trap vast stores of carbon in layers of frozen organic soil up to a mile thick.

By some estimates, even though permafrost located below the Arctic tundra and shallow subsea shelves store a smaller portion of the methane in the Arctic at about 1%, compared to the 99% found in marine sediments, shallow subsea and surface exposed Arctic permafrost is estimated to contain enough carbon and other greenhouse gases to nearly double the amount of CO2 currently in the Earth’s atmosphere.

By 2200, it is estimated that about two-thirds of the Earth’s permafrost will have melted, releasing an estimated 190 billion tons of carbon dioxide and methane into the air, according to Dr. Kevin Schaefer at NSIDC. Further, he says “all our emission reduction strategies are designed to hit a target atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration corresponding to a target climate. If we do not account for carbon released from thawing permafrost, we will overshoot this target concentration and end up with a warmer climate than we want.”

Additionally, the authors of this study found that if humans continue on the current path of energy use, the permafrost could release as much as 92 gigatons of carbon into the atmosphere by the end of this century. That represents nearly 18% of what the world has emitted since the start of the Industrial Revolution—or more than one third of what can be safely burned and still keep global warming within 2°C, the commonly cited safety threshold.

There are many interesting mechanisms that act as conduits of methane escape from permafrost into the atmosphere including ebullition lakes, thaw lakes, thaw ponds, seeps, slumps, thermal erosion, pingos, polynyas, and more. Further according to Katey Walter, Scientist at the University of Alaska, “one molecule of methane is like 25 molecules of carbon dioxide, so it’s a really strong greenhouse gas, contributing to climate warming and making the warming that’s already happening worse. If we can slow down climate warming it will slow down permafrost thaw, which will cause less of a temperature increase. If we speed up climate warming and permafrost flash thaws, we will have a huge pulse of greenhouse gases, especially methane, going into the atmosphere that will cause a really abrupt warming.” In the following video, Katey Walter introduces this very real threat:

Walters goes on to say that “the mechanism of abrupt thaw and thermokarst lake formation matters a lot for the permafrost-carbon feedback this century. We don’t have to wait 200 or 300 years to get these large releases of permafrost carbon. Within my lifetime, my children’s lifetime, it should be ramping up. It’s already happening but it’s not happening at a really fast rate right now, but within a few decades, it should peak.”

Permafrost (video) is already expressing its stress in measurable data. NASA-funded research has discovered that Arctic permafrost’s expected gradual thawing and the associated release of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere may actually be sped up by instances of a relatively little known process called abrupt thawing. Additionally, the rate of permafrost thawing has not been adequately incorporated into existing climate models. Arctic permafrost is thawing fast. That affects us all.

Abrupt thawing takes place under a certain type of Arctic lake, known as a thermokarst or thaw lake that forms as permafrost melts creating seeps and bubbling ebullition lakes where greenhouse gases can escape. Having surveyed Arctic regions using airplanes and field expeditions, more than 150,000 seeps have been identified by scientists.

NASA researchers used measurements from 11 thermokarst lakes and computer models to show that abrupt thawing will result in more than double previous estimates of the warming from the thawing permafrost. They found methane bubbling at 72 locations within these lakes, measuring the amount of gas being released by the permafrost beneath the water.

Further, Ted Schuur, a permafrost expert at Northern Arizona University has said that “a rapid meltdown would be disastrous because it could release a lot of CO2—in addition to methane, a powerful short-lived climate pollutant—to the atmosphere, where it would cause additional warming. (…) This rate of warming suggests substantial change underway.” In this study Schuur estimates 5-15% of the Arctic methane budget may be susceptible to release by 2100.

The oceans over the shallow continental shelves in the Russian Arctic (ESAS, Laptev) were once ice covered, keeping the ocean shelves near freezing temperatures under the polar surface waters (at depths of ~150m or less). Since 2005, the ice cap cover has gone. The water has warmed as high as 17°C there in summer up from freezing at 0°C, heating the sea-floor, perforating the permafrost cap, and thawing methane hydrates. Ebullition (bubbling methane) is rising up the water into the atmosphere in ever increasing amounts. The more permafrost melts, the more methane is released.

The ESAS and other continental shelves are at shallow depths (less than 50-100 M). Most of the methane already being released is escaping into the atmosphere from subsea permafrost located on these shelves rather than being absorbed into water. The existence of such shallow methane hydrates in permafrost was confirmed here at depths as small as 20m according to this Nature study. How much is there is still in question. According to this same study, “a challenge for assessing the impact of contemporary climate change on methane hydrates is continued uncertainty about the size of the global gas hydrate inventory and the portion of the inventory that is susceptible to climate warming.”

Additionally, hydrates are not ubiquitous throughout permafrost areas and much more study is needed to determine how much is there and where it is located. But there is no question the quantities here are enormous. This study by Streletskaya et al attempts to estimate the amount of methane in various types of permafrost and ground ice and has reported methane concentrations of up to 8.5 million ppb in permafrost on Yamal Peninsula alone. The study states that “the mean isotopic composition of methane is −68.6‰ in permafrost.” Much more research is needed to determine how much methane is located in Arctic region in total.

In any case, what is clear is that these shallow and terrestrial gas hydrate sources are degrading as ocean and air temperatures warm faster than expected. According to Streletskaya et al “permafrost degradation due to climate change will be exacerbated along the coasts where declining sea ice is likely to result in accelerated rates of coastal erosion, especially in areas with presence of massive tabular ground ice (MTGI), further releasing the methane which is not yet accounted for in the models.”

Arctic permafrost is showing dangerous signs of degradation and thaw. Recently the seed vault library in Svalbard was flooded for the first time after permafrost melted. No one ever thought this could happen. Never-before-thought-possible climate catastrophes are playing out right in front of us. These bizarre phenomena one after another provide the evidence unfolding before our eyes of a man-made methane emergency; yet we as a global society remain dangerously mired in political inaction, cognitive dissonance, and confirmation bias.

Methane in Marine Sediments: The Monster

Methane in permafrost and other terrestrial areas is a completely different issue than subsea methane stored in marine sediments deep in the ocean floor.

Today it is assumed that in the worst case, with a steadily warming ocean, around 85% of the methane trapped in the deep sea floor (the other 99%) could be released into the water column. In some locations, researchers claim that a temperature increase of only 1°C would be sufficient to release large amounts of methane from hydrates all at once.

Read further >> Debunked: Methane Monster

Act now >> Ask the EPA and other regulatory agencies to cut methane emissions.

_____________________________________________

Learn more:

- Arctic Methane Emissions

- Rewilding the Arctic Could Stop Permafrost Thaw

- Permafrost is Thawing So Fast, It’s Gouging Holes in the Arctic

- Permafrost and Neoliberalism Hit a Grim Threshold

- Defusing The Methane Time Bomb | Scientific American

- Mann & Hansen on the Methane Time Bomb

- Methane Emissions Underestimated | Science Daily

- Methane Releases Much Larger/Faster | NSD

- Methane Levels May See ‘Runaway’ Rise | Independent

- Methane Video Lectures | Paul Beckwith

- Some Methane Emissions Could Slow Warming | Grist

- Urgent Need to Reduce Methane Emissions | EDF

- What Scientists Know About the Methane Bomb | Seeker

- Seven Facts You Need to Know About the Arctic Methane Timebomb | The Guardian

- Methane Increase over the Barents and Kara Seas After the Autumn Pycnocline Breakdown: Satellite Observations

Conclusions

Methane needs further research on many fronts. In the meantime, scientists at Yale Climate Connections are asking that we begin to distinguish between the larger real-world methane threat already underway, and a theoretical methane monster.

Climate models project a temperature increase of around 4ºC by 2100 if we fail to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, including methane — and that alone should present us with enough of a deeply troubling scenario to act now.

What happened to the dinosaurs, can happen to us. We have entered a danger zone never before encountered by modern man. Most researchers agree that we must declare a methane emergency as well as a climate emergency now. It’s time to bring scientists, policy makers, and people together to focus on translating research into action.

Unfortunately, we are currently locked in a deadly stalemate as world leaders have never declared that climate change is even happening let alone that it is a global emergency – which is why those seeking climate justice, such as eXtinction Rebellion, are demanding that elite powers at long last tell citizens the truth about the disastrous situation we are facing.

As a global species we are playing with fire while we lose the ancient ice that is our planetary cooling mechanism. If we continue on this path, the current indisputable evidence puts us on a fast track toward a hellish, Venus-like greenhouse Earth.

__________________________________________________________________

References:

- AMAP (2015). AMAP Assessment 2015: Methane as an Arctic climate forcer. Retrieved from https://www.amap.no/documents/doc/amap-assessment-2015-methane-as-an-arctic-climate-forcer/1285

- Archer, David (2014) The story of methane in our climate, in five pie charts. Retrieved from http://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/2014/09/the-story-of-methane-in-our-climate-in-five-pie-charts/

- Doomsday Debunked (2019). Clathrate gun hypothesis. Retrieved from https://doomsdaydebunked.miraheze.org/wiki/Clathrate_gun_hypothesis

- EPA (2016). Climate change indicators: climate forcing. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/climate-indicators/climate-change-indicators-climate-forcing

- Guardian (2013). 7 facts you need to know about arctic methane. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/environment/earth-insight/2013/aug/05/7-facts-need-to-know-arctic-methane-time-bomb

- Geophysical Research Letters (2019). Very strong atmospheric methane growth in the four years 2014‐2017. Retrieved from https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2018GB006009

- Geophysical Research Letters (2016). The interaction of climate change and methane hydrates. Retrieved from https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/2016RG000534

- Harris, William (2019). Fire and ice: the chemistry of methane hydrate. Retrieved from https://science.howstuffworks.com/environmental/green-tech/energy-production/frozen-fuel1.htm

- IPCC (2013). Climate change 2013: The physical science basis. Retrieved from http://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg1

- Leifer, Ira (2013). Methane emissions higher than thought across much of U.S. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2013/05/130515165021.htm

- NASA (2019). A global view of methane. Retrieved from https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/87681/a-global-view-of-methane

- National Geographic (2012). Antarctica methane. Retrieved from https://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2012/08/120831-antarctica-methane-global-warming-science-environment/

- Nature (2018). Trajectories of the Earth system in the Anthropocene. Retrieved from https://www.pnas.org/content/115/33/8252

- Nature (2017). Enhanced CO2 uptake at a shallow Arctic Ocean seep field overwhelms the positive warming potential of emitted methane. Retrieved from https://www.pnas.org/content/early/2017/05/02/1618926114

- Nature (2013). Eemian interglacial reconstructed from a Greenland folded ice core. Retrieved from https://www.nature.com/articles/nature11789

- NOAA (2016). The NOAA annual greenhouse gas index. Retrieved from http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/aggi

- Phys.org (2017). Study finds hydrate gun hypothesis unlikely. Retrieved from https://phys.org/news/2017-08-hydrate-gun-hypothesis.html

- Reviews of Geophysiscs (2017). Methane feedbacks to the global climate System in a warmer world. Retrieved from https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/2017RG000559

- Schuur, Ted (2019). Permafrost is warming around the globe study shows. Retrieved from https://insideclimatenews.org/news/16012019/permafrost-thaw-climate-change-temperature-data-arctic-antarctica-mountains-study

- Scribbler, Robert (2018). Analysis of present surface temperature hot spots. Retrieved from https://robertscribbler.com/tag/methane/

- Streletskaya et al (2018). Methane content in ground ice and sediments of the Kara Sea Coast. Retrieved from https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3263/8/12/434/htm?fbclid=IwAR2Pc_A01J1iEdsg6_pTbhAooY1IkkFsnH0JxoD8qey6Lh8czrU9CoYcCIc

- UC – Santa Barbara (2013). Methane emissions higher than thought across much of U.S. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2013/05/130515165021.htm

- Walter, Katey (2018). Arctic cauldron. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2018/national/arctic-lakes-are-bubbling-and-hissing-with-dangerous-greenhouse-gases/

- Yale Climate Connections (2019). Methane hydrates: why scientists worry less than you might think. Retrieved from https://www.yaleclimateconnections.org/2019/02/methane-hydrates-what-you-need-to-know/?fbclid=IwAR2oV-Fh6STDzCfqmQg6-gbCarUZUKPU7HqOP-hdW9f8-UCJcneKODkIXwY

__________________________________________________________________

Last Updated: 01/01/2022